In a manner of speaking, this is a #ThrowbackThursday post. Not that it’s been posted before, but I started writing it exactly two years ago, on our last trip out of the country. Somehow, with the lockdown and everything, I never had the heart to finish it, but now, on the second anniversary of the trip, it seemed like a good time to dust it off and put it up. Now that things are opening up again, maybe it’ll be possible to go back there soon?

I was just on another jaunt to the Old Country. As I’ve said before, while living halfway across the globe from your family can be a pain in the neck (literally – those long flights are uncomfortable), a visit also makes for good opportunities to get in some sightseeing.

This time, I got to see the Dickens Museum at 48 Doughty Street in London*. Charles Dickens (whom, courtesy of Roald Dahl and his BFG, I am now always thinking of as Dahl’s Chickens) lived in this house in Bloomsbury from 1837 – 1839, at the very beginning of his writing career. He moved in as an unknown 25-year-old with a wife and one baby, and moved out two years later as a popular writer with two more children and an established name.

Now, I’m not a die-hard Dickens fan – truth be told, I’ve only read about half a dozen of his books so far. But this museum was fascinating in a way that wasn’t even directly about him. The house is a testament to the life of a middle-class family in the very earliest years of Victoria’s reign.

The Dickens family consisted of one young man (Twenty-five! He was just twenty-five!), his wife, her sister, and one-two-three babies. They had: on the ground floor, a dining room and morning room (basically Mrs Dickens’ office or place to hang out); on the first floor a drawing room and Dickens’ study; on the second floor two bedrooms (one for the Dickenses and one for sister-in-law); on the third floor, the nursery and servants’ bedroom; in the basement, the kitchen, scullery, and wash house (laundry room). That’s it.

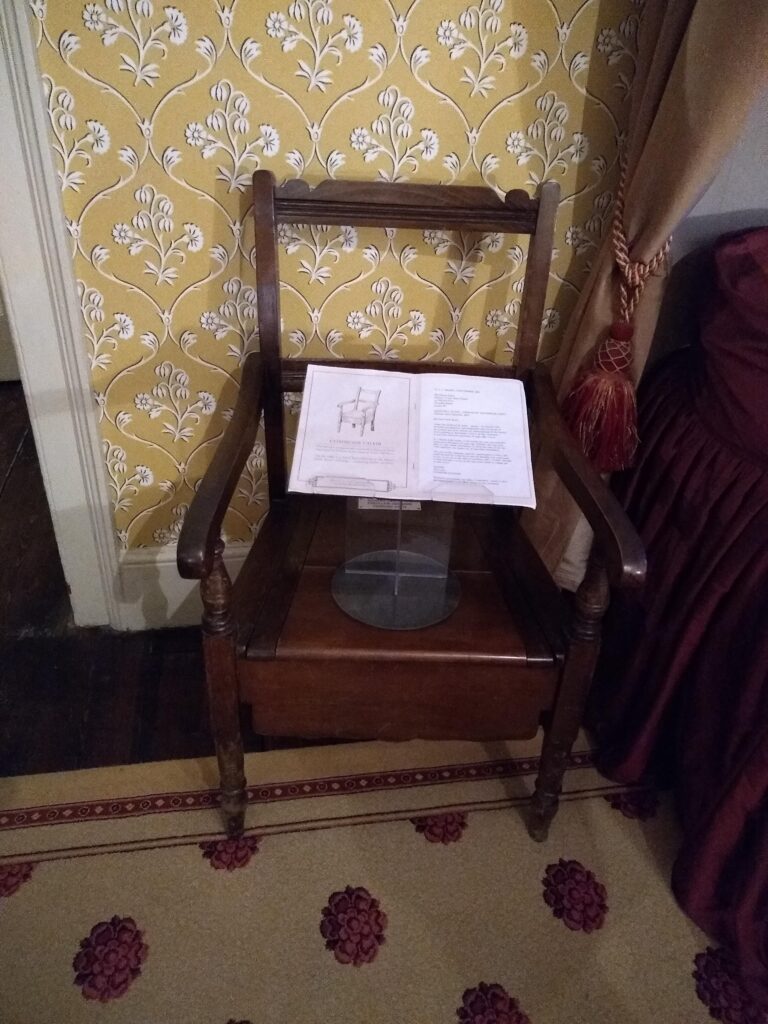

“Oh, but of course the bathrooms, too,” you say? No. No bathrooms. No toilets**. No sinks, no places to wash hands, except for one stone sink in the basement scullery. So where did they do their, you know, business?

On chamberpots (ceramic bowls large enough to sit on) and commodes, which are basically chairs with a hole in the seat and a potty under it. And you guessed it: somebody had to empty them out. Somebody had to carry porcelain bowls full of smelly, stinky, gross you-know-what down three flights of stairs and dump them.

And that same somebody also got to lug pots full of hot water up the stairs every morning so the family could have a wash. In fact, if Mrs Dickens wanted a bath, she had it in front of the fire in her bedroom. The tub on display at the museum is a little hip bath – small enough that it can be carried while full. Let me repeat that: a tub full of water—let’s say, at a minimum five to ten gallons, or twenty to forty litres/kilos—carried down three flights of stairs. With how small people were in those days, that’s probably half the body weight of the person who had to do the carrying.

The maid who had to do the carrying. Because it sure wasn’t Mr Dickens himself, or his wife, or his sister-in-law.

Hence the servants’ bedroom on the third floor. The young Dickens family in that Doughty Street house, an ordinary middle class family whose sole wage earner was at the beginning of his career, consisted not only of Mr, Mrs, Miss, and Babies, but also a cook, a house/parlour maid, and a nanny. And they needed those servants, because without them, things would have been pretty darn uncomfortable. Servants’ wages and room and board were a normal part of the expenses of any middle class household; not having servants, i.e. having to do the work yourself, was the very definition of “working class.”

I had never really thought about that before. Indoor plumbing with hot and cold water at the push of a button is something we take for granted today; central heating and electric stoves and washing machines and vacuum cleaners are something we don’t even think about.

But in Dickens’ time, indoor plumbing was provided by the servants carrying jugs and buckets and tubs full of water and sewage up and down stairs. Heat to keep you warm and to cook with (Every. Single. Cup of tea!) and hot water to wash or bathe in were supplied by the servants lighting and stoking and cleaning out and re-lighting fireplaces. The scrubbing action and spin cycle of the washing machine came from the servants rubbing and plungering and wringing laundry in the cold stone-flagged wash house in the basement, and the vacuuming of carpets was accomplished by the servants lugging them out back and beating the dirt out of them with a carpet beater.

A lot of us (myself included) have this nostalgia for the days of the past, would like to spend our imaginary lives back in the days “when life was simple,” want to hang out with Elizabeth Bennet and Mr Darcy and Ebenezer Scrooge (once he got his head screwed on straight). But life “in those days” actually wasn’t simple—it was quite complex. And it was almost entirely human-powered. We measure a car’s engine in horsepower—maybe we should measure indoor plumbing and electric washing machines in human-power (“This latest model of Maytag has a 5hu-p/day capacity and is able to draw 8hu-p of hot water in less than two minutes…”).

I’m not going to give up mentally living in the past, but visiting the Dickens Museum has given me a whole new appreciation for just how privileged we are today. Next time you flush the toilet in your second-floor bathroom or crank the handle in the tub to instantly have hot water raining on your head, give a thought to that unnamed woman who, 185 years ago, carried enormous buckets full of water and slop up and down the steep stairs of a small London house, so that a gifted young man could sit in his study and write wonderful stories about Oliver Twist and Nicholas Nickleby that are still with us today.

Life, the Universe, and Indoor Plumbing. Charles Dickens would have been nothing without his servants.

*I can highly recommend the website of the Dickens Museum at https://dickensmuseum.com. Lots of interesting information, and you can take a whole virtual tour of the museum, including admiring the hip bath by the bedroom fire!

**2022 addition: Apparently, as I just found out, there was actually one “water closet” (toilet) on the ground floor and one in the basement, but firstly, that was a new and unusual thing for the day, and secondly, the servants still had to carry all the wash water and chamberpot waste up and down the stairs to the upper floors.